I’ll call you, and we’ll light a fire, and drink some wine, and recognise each other in the place that is ours. Don’t wait. Don’t tell the story later.

– Jeanette Winterson, Lighthousekeeping

I keep thinking of how to begin this piece. I have written many words, a whole separate essay, and scrapped them all. Nothing seems to be the right beginning; no word seems to be of use. And so perhaps it would do it good to begin with the ending instead, which is that I am here in Cambridge, Massachusetts on the last week of my three-week visit to my friend while I am in the middle of a major life transition. It is late autumn, and most trees are already bare. The weather fluctuates – odd warm days and biting cold nights. It gets dark at half past four; the nights stretch on forever.

I am reeling from / processing / grieving a relationship that ended two days after I’d arrived here. I could get into the semantics of that word – ‘relationship’ – but I maintain that it was. J. and I did not put a concrete label on what was occurring between us, and perhaps the fact that I am writing about this now is telling of the slipperiness of meaning and language and also of our stubbornness and naivete. We had gone beyond interpretation, was what I told myself and everyone else who listened. And it seems that even at the ending of things we manage to elude it so. I am struggling to write about it because I do not want to fall into the trap of turning every experience into a teacher. I resist putting a neat little ribbon around this loss, declaring, ‘Welp! It’s done now. It was beautiful and it meant so much, but it is done now.’ I do not want to diminish this love by turning it into a lesson. In As Consciousness is Harnessed to Flesh: Journals and Notebooks, 1964-1980 (Penguin, 2012), Susan Sontag writes:

[In the margin]: I don’t want to learn anything from the failure of this love.

(What I could learn is to become cynical or guarded or even more afraid of loving than I was before.) I don’t want to learn anything. I don’t want to draw any conclusions. Let me go on being naked. Let it hurt. But let me survive.

That is what I want, too: to hurt, and alongside that hurt, to survive.

There is no exact moment when I fell in love with J. Whether that happened early on or much later, I can’t tell. Perhaps somewhere in between. Relationships are hard to encapsulate. They are their own universe known only to the people inside them who share an exclusive lexicon. This is part of what makes them so unique. Who is it who said something about how lovers are quite literally in each other’s tongue?

It wasn’t difficult to develop our own language. On our first couple of dates, J. and I asked each other: ‘Do we actually want to be fully known?’ I read to him an excerpt from Tim Kreider’s article on The New York Times, the one that has been perpetually quoted from online to emphasise our collective fear of vulnerability:

Years ago a friend of mine had a dream about a strange invention; a staircase you could descend deep underground, in which you heard recordings of all the things anyone had ever said about you, both good and bad. The catch was, you had to pass through all the worst things people had said before you could get to the highest compliments at the very bottom. There is no way I would ever make it more than two and a half steps down such a staircase, but I understand its terrible logic: if we want the rewards of being loved we have to submit to the mortifying ordeal of being known.

That conversation may have set a precedent for us. There was a sense of opening then, even in our first meeting, a sort of implied invitation into a space we could enter that was safe, deferring judgment and welcoming vulnerability. J. and I basked in the beauty of this. There was so much we wanted to say to each other, so much ease. He told me once that there were so many parts of him that wanted to come out with me, that I got him all figured out. I think these were early hints that my presence in his life was drawing him out, that there was something about ourselves within that connection that was visible and persistently so, despite our best efforts to hide.

I am reminded of Shel Silverstein’s ‘The Thinker of Tender Thoughts’. The idea is that due to other people’s judgment, the thinker of tender thoughts chooses to cut the flowers on his head, therefore, becoming like everyone else. It is a tragic outcome. If J. and I were in this illustration, there would be no need for harsh pruning. With each other, we kept sprouting blossoms. At least, that’s how I think of it. To him, I was a catalyst for self-discovery, as if he was a tree that didn’t know he could grow fruits. With him, I felt expansive. I was growing veins, climbing walls, extending beyond myself, a little larger than life. He made me feel that way: magnified. He ascribed strengths to me that I wasn’t sure I had. Conversations with him were endless, generative, created ripples of themselves, made my brain juice flow in many directions. He asked interesting questions. He is smart and deeply curious not just about my world, but everything and everyone else, too. He has such an appetite for life. He was unremitting in his efforts, with his goals, and he continuously surprised me with his capacity for growth. He always met me at the level I was at: in terms of depth, humour, playfulness, analysis, reflection. Even though sometimes it challenged and pained him, he took me seriously – no emotion nor issue nor thought was too small or big.

J. and I, sometimes to our disappointment, reflected ourselves back to each other. Our differences heightened this, too, for what are differences but only the shadow parts of ourselves? He was pragmatic; I was romantic. He was calculating; I was impatient. He was strict with his sleep schedule; I stayed up late. He battled with his desires; I took pleasure in mine. ‘You know me too well,’ we sometimes found ourselves saying. Some of the things he knows about me: how I like my coffee; how I care about how my hair looks; that at night I could only drink tea in a small cup; that I unknowingly repeat myself when making a point. Some of the things I know about him: that he wears long johns at home; how his next-day clothes would be folded on his bed the night before; how deep his laughter is when watching Seinfeld clips; how he tells the full plot of a film he has watched; his bravado; his resilience; the way he rejects paved paths to search for what feels truer to him.

Once, I read that it takes three years to fully know someone, factoring in, of course, the frequency and quality of time spent together, the various contexts in which we see parts of another person. I was obsessed with this notion that there was a specific time period, by the end of which I would reach the utopia of knowing someone. But it is a myth; you can’t fully know someone nor would you want to. People are like crystals, I suppose. Rotate them in the light and they will surprise you with another angle, beauty, flaw. An inexhaustible depth.

It can be confronting, though, to see yourself through someone else’s eyes. It is not guaranteed that what someone sees of us is how we want to be seen. J. and I had a few conversations that turned to disagreements because of this – of the ways in which we saw each other that were glaringly honest and real and did not align with the way we wanted to see ourselves. Sometimes we saw too much that we ended up seeing through the other. All of these were only perceptions, it’s true. In Henrik Karlsson’s ‘Dostoevsky as lover’, he writes of his wife:

A person can’t be contained in your ideas about them. This was a core idea for us. To whatever extent I assumed I knew who Johanna was, I treated her as something that I could fit in my head – as something smaller than me. But she couldn’t fit in my head, nor I in hers: that was the exciting thing about it. You can only ever know another individual if you meet them in open dialogue – if you treat them as unfinished, as capable of surprise.

J. and I were prone to this – to the attempt of fitting each other in our heads – and we hurt each other this way when we were unable, in certain moments, to allow our imagination of the other to go beyond. Because I do believe that love, as much as it involves the real, involves the imaginary, too. It is a particular kind of hope – to hold back some of our preconceived ideas of the other (and ourselves) and be generous in holding out for bewilderment and wonder.

In any case, J. and I always came through the other side of conflict because we were so good at talking. Not communication per se – although I would argue that we were also good at that – but the process of excavation, this ‘willingness for research’, as Elizabeth McCracken puts it. J. saw in me a rich world, and I thought the world of him, still do. We were steadfast in our unspoken belief that neither of us had a genuine want of causing the other pain. Wendell Berry, in his interview that I often return to, says of him and his wife: ‘I’m in a conversation with her that hasn’t ended yet. It’s either that or kill each other.’

We live on – we were lucky to avoid destroying each other – although our conversations have since ended and that, in itself, took excruciating effort; was its own kind of murder.

My friend in Cambridge showed me a book by one of her favourite artists, Sophie Calle. The book is called Exquisite Pain. It is a recollection of Calle’s heartbreak while on a trip in Japan in 1984, after she was awarded a grant for a three-month scholarship. Ninety-two days since her departure from France, her boyfriend failed to show up in New Delhi, where they had planned to meet. She returned to France in February 1985, and embarked on an experiment. She began asking friends and strangers, ‘When did you suffer most?’ She writes: ‘I decided to continue such exchanges until I had got over my pain by comparing it with other people’s, or had worn out my story through sheer repetition.’

I had come upon the book two days before it ended with J. Did I already sense that we would separate? We knew from the beginning that there was a taut string between us. That at some point, it would break, although I hoped against it. We wanted so much, he said to me once on a long-distance phone call. I sent to him Jack Gilbert’s poem ‘Failing and Flying’: But anything that is worth doing is worth doing badly. By the time it finally ended between us, we’ve already had a handful of attempts at separation. Every time we completely believed it was the last. It makes me shake my head when I think of this. It is our version of ‘doing things badly’. As if we were trying to perfect our break-ups, wearing it out ‘through sheer repetition’, to borrow from Calle. But of course, each time was no easier or less painful than the last.

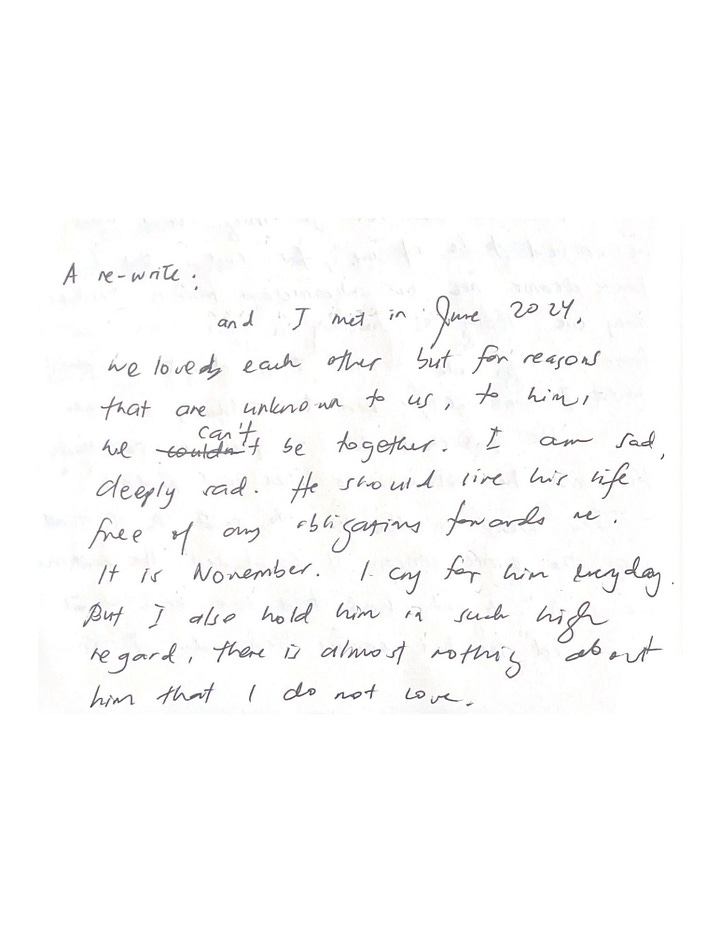

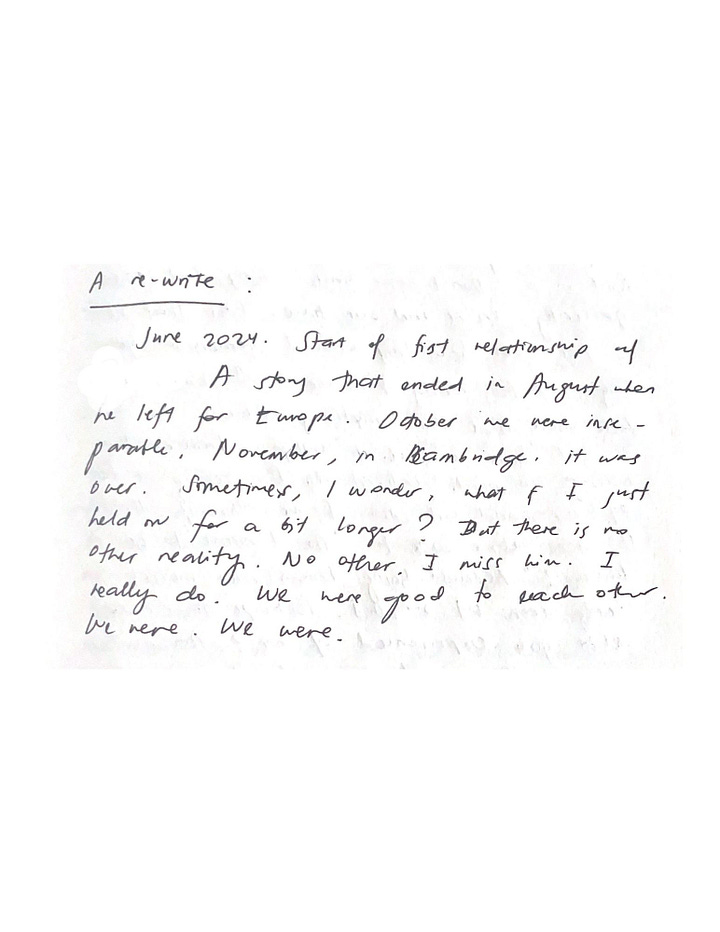

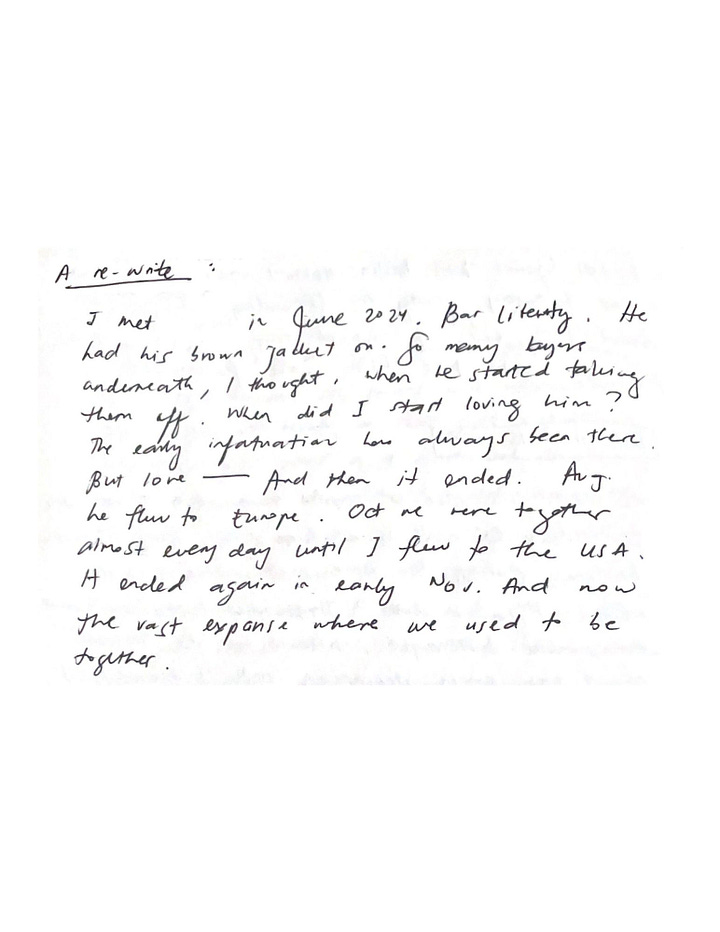

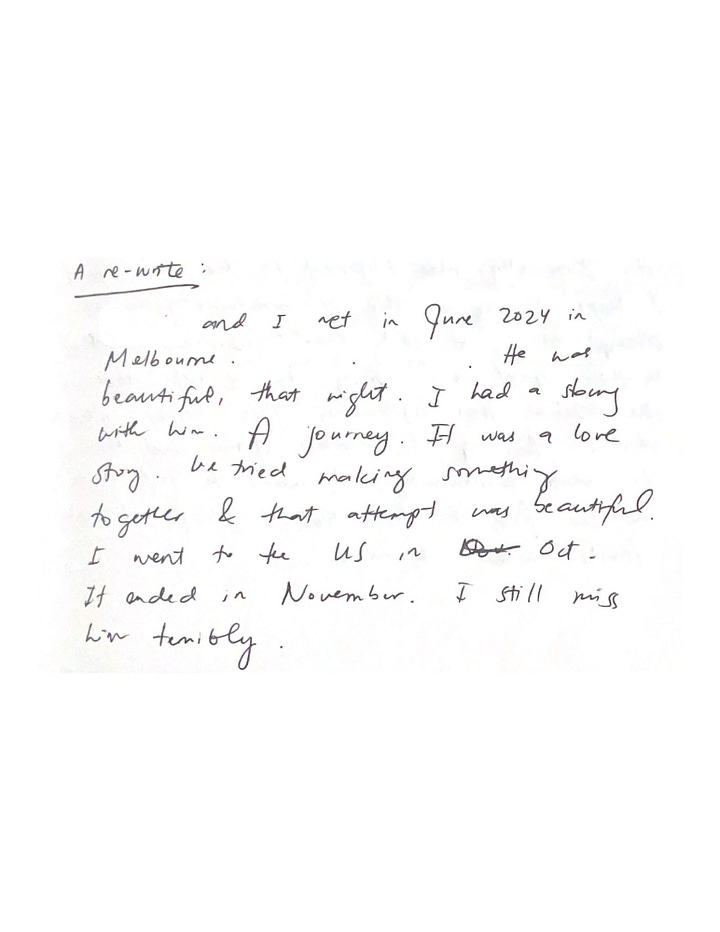

Inspired by Calle’s work, I started writing (telling myself) our story in my journal. I needed to see the narrative flat on a surface so it was more manageable. This became a daily practice, completely separate from the other entries, which were also – sadly, hopelessly – mostly about J. Sheer repetition, Calle says. I was less concerned about my pain than my sense of narrative. What would change as I keep retelling the story? What would stay? What subtleties would be removed when I begin with a fact? How would words be (re-)arranged? How much of the same thing could I regurgitate? What would I bend and forget and fabricate and insist on? Would I hammer it down to extinction? That last one I am afraid of the answer. I don’t want the pain to disappear; I only want to put it down.

There are patterns in these mini stories. I always begin with the day we met, which was almost six months ago now. The timeline seems important to me, as if I could anchor my reality in the flow of things. These are the facts, the months, the places; they are indisputable, they seem to say. Time has always been a cunning player in our story. We often lost track of it, had little of it, were running against it, losing it while experiencing it. There is also distillation in my narrative. Gone are the minutiae for the most part. What remains is the bigger picture. I think these are more generous, more forgiving. But who am I to say? In each of them, I acknowledge the loss, the grief, the end. In each of them, I speak him into existence.

Much like the beginning of this piece, I do not know where or how to end this. I would like to think that J. and I avoided destroying each other by letting each other go the way we did. It was the kind thing to do, we agreed. But a part of me couldn’t help but wish that I was not spared the destruction, or at least the risk of it. There would be glory and courage in that. But that is another story; one we didn’t live.

In a few days, I will be going back to Texas. I will lie down on the bed where I spoke to J. many times through phone and video calls. I still speak to him sometimes in my head, telling him stories that he would never hear. For all my cries of not knowing the right words, I have written so much here and yet they are still not enough. They are only an approximation of him, of the story we created. What I have done here is pure translation of what transpired between us. This is the challenge of trying to speak the unspeakable: in the end language falls short.

I find solace in the memories. They are double-edged, of course. The way his voice sounded in the morning/night-time when he was telling me tender things about himself; how he let me (and loved seeing me) sleep in his underwear when I stayed the night; how he started stories with, ‘One time…’; all our walks, meals together, the playground where we sat like children on the swings in the middle of the night. We had a running joke about my loud phone alarm, too; that it would wake not only me but also his neighbours. Then when we were already sixteen-hours apart, he said to me: ‘I would give a lot for that alarm to be going off my face if it meant you were here.’

Too many memories. Too little sense. How can I put it down? When I think of him, I think of the way he looked when I made him laugh (God, I loved making him laugh): the opening of his face, the spread of bright smile, his eyes crinkling, his mouth a well of beauty, all the goodness in him coming up to the surface.

Nothing,

nothing.

There is no meaning I want to derive from this love but that.

Links / readings:

Tim Kreider, ‘I Know What You Think of Me’, The New York Times (15 June 2013).

In his blog Escaping Flatlands, Henrik Karlsson wrote a three-part series on love. It is such an engaging, thought-provoking read as he reflects on his love story with his wife, Johanna. (Part one: Looking for Alice; Part two: Dostoevsky as lover; Part three: Relationships are co-evolutionary loops)

Elizabeth McCracken, The Giant’s House (1996).

Amanda Petrusich, ‘Going Home with Wendell Berry’, The New Yorker (14 July 2019).

Jack Gilbert, ‘Failing and Flying’, Refusing Heaven (2005).

I have also read and loved this beautiful and moving essay called ‘Against narrative: a love story, or an essay about love stories, or the opposite of both’ by Rayne Fisher-Quann.